Classification of groups of prime-cube order: Difference between revisions

(g) |

|||

| (16 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Let <math>p</math> be a [[prime number]]. Then there are, up to isomorphism, five groups of order <math>p^3</math>. These include three abelian groups and two non-abelian groups. The nature of the two non-abelian groups is somewhat different for the case <math>p = 2</math>. | Let <math>p</math> be a [[prime number]]. Then there are, up to isomorphism, five groups of order <math>p^3</math>. These include three abelian groups and two non-abelian groups. The nature of the two non-abelian groups is somewhat different for the case <math>p = 2</math>. | ||

{{quotation| | {{quotation|For more information on side-by-side comparison of the groups for odd primes, see [[groups of prime-cube order]]. For information for the prime 2, see [[groups of order 8]]}} | ||

===The three abelian groups=== | ===The three abelian groups=== | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

For the case <math>p = 2</math>, these are [[dihedral group:D8]] (GAP ID: (8,3)) and [[quaternion group]] (GAP ID: (8,4)). | For the case <math>p = 2</math>, these are [[dihedral group:D8]] (GAP ID: (8,3)) and [[quaternion group]] (GAP ID: (8,4)). | ||

For the case of odd <math>p</math>, these are [[ | For the case of odd <math>p</math>, these are [[unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p)]] (GAP ID: (<math>p^3</math>,3)) and [[semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order]] (GAP ID: (<math>p^3</math>,4)). | ||

==Related facts== | |||

* [[Classification of nilpotent Lie rings of prime-cube order]] | |||

* [[Classification of groups of prime-square order]] | |||

* [[Classification of Lie rings of prime-square order]] | |||

==Facts used== | ==Facts used== | ||

{{fact used table disclaimer}} | |||

{| class="sortable" border="1" | |||

! Fact no. !! Statement !! Steps in the proof where it is used !! Qualitative description of how it is used !! What does it rely on? !! Difficulty level !! Other applications | |||

|- | |||

| 1 || [[uses::Prime power order implies not centerless]] || Step (CD1) || Eliminates the case of trivial center || [[class equation of a group]] || {{#show: prime power order implies not centerless|?Difficulty level}} || {{uses short|prime power order implies not centerless}} | |||

|- | |||

| 2 || [[uses::Center is normal]] || Steps (CD2), (CD4) || Used to note that the quotient by the center exists as a group || || {{#show: center is normal|?Difficulty level}} || {{uses short|center is normal}} | |||

|- | |||

| 3 || [[uses::Cyclic over central implies abelian]] || Steps (CD2) (CD4) || Rules out the possibility of center of order <matH>p^2</math>, helps determine nature of quotient group if center has order <math>p</math> || ||{{#show: cyclic over central implies abelian|?Difficulty level}} || {{uses short|cyclic over central implies abelian}} | |||

|- | |||

| 4 || [[uses::Lagrange's theorem]] || Step (CD2) || Narrows down possibilities for order of center, and allows for computation of order of quotient group || ||{{#show: Lagrange's theorem|?Difficulty level}} || {{uses short|Lagrange's theorem}} | |||

|- | |||

| 5 || [[uses::Equivalence of definitions of group of prime order]]: This basically states that any group of prime order must be cyclic. || Steps (CD2), (CD4) || Helps rule out center of order <math>p^2</math>, helps determine isomorphism class of center of order <math>p</math> || ||{{#show: equivalence of defintiions of group of prime order|?Difficulty level}} || {{uses short|equivalence of definitions of group of prime order}} | |||

|- | |||

| 6 || [[uses::Classification of groups of prime-square order]] || Step (CD4) || Narrows down possibilities for quotient by the center once we have determined that the center has order <math>p</math> || ||{{#show: classification of groups of prime-square order|?Difficulty level}} || {{uses short|classification of groups of prime-square order}} | |||

|- | |||

| 7 || [[uses::Structure theorem for finitely generated abelian groups]] || Classification of abelian groups case || || ||{{#show: structure theorem for finitely generated abelian groups|?Difficulty level}} || {{uses short|structure theorem for finitely generated abelian groups}} | |||

|- | |||

| 8 || [[uses::Class two implies commutator map is endomorphism]] || '''Case B''' analysis || Helps reduce general case to a specific presentation by a change of variable || ||{{#show: Class two implies commutator map is endomorphism}} || {{uses short|class two implies commutator map is endomorphism}} | |||

|- | |||

| 9 || [[uses::Formula for powers of product in group of class two]] || '''Case C''' analysis || Helps reduce Case C to Case B by a change of variable || || {{#show: Formula for powers of product in group of class two}} || {{uses short|Formula for powers of product in group of class two}} | |||

|} | |||

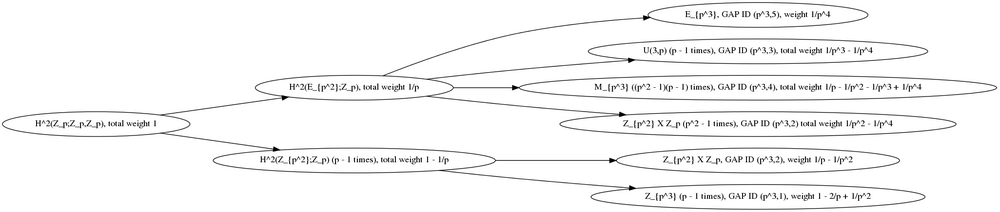

==Cohomology tree== | |||

This can be formulated as an alternative proof if we prove assertions for each of the cohomology groups. | |||

===For odd primes=== | |||

[[File:Cohomologytreeoddprimecubeordergroups.png|1000px]] | |||

The cohomology groups governing the branchings are as follows: | |||

* [[Second cohomology group for trivial group action of group of prime order on group of prime order]] controls the initial branching from the root. | |||

* [[Second cohomology group for trivial group action of elementary abelian group of prime-square order on group of prime order]] controls the upper second level branching. | |||

* [[Second cohomology group for trivial group action of cyclic group of prime-square order on group of prime order]] controls the lower second level branching. | |||

===For the prime 2=== | |||

This is for groups of order 8: | |||

[[File:Cohomologytreeorder8groups.png|1000px]] | |||

The cohomology groups governing the branchings are as follows: | |||

* [[Second cohomology group for trivial group action of Z2 on Z2]] controls the initial branching from the root. | |||

* [[Second cohomology group for trivial group action of V4 on Z2]] controls the upper second level branching. | |||

* [[Second cohomology group for trivial group action of Z4 on Z2]] controls the lower second level branching. | |||

==Proof== | ==Proof== | ||

{{tabular proof format}} | |||

===First part of proof: crude descriptions of center and quotient by center=== | ===First part of proof: crude descriptions of center and quotient by center=== | ||

| Line 51: | Line 98: | ||

! Step no. !! Assertion/construction !! Facts used !! Given data used !! Previous steps used !! Explanation | ! Step no. !! Assertion/construction !! Facts used !! Given data used !! Previous steps used !! Explanation | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CD1 || <math>Z</math> is nontrivial || Fact (1) || <math>P</math> has order <math>p^3</math>, specifically, a power of a prime || || Fact+Given direct | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CD2 ||The order of <math>Z</math> cannot be <math>p^2</math> || Facts (2), (3), (4), (5) || <math>P</math> has order <math>p^3</math> || || <toggledisplay><math>P/Z</math> exists by fact (2) and has order <math>|P|/|Z|</math> by fact (4). If <math>Z</math> has order <math>p^2</math>, the order of <math>P/Z</math> is <math>p^3/p^2 = p</math>. By fact (5), <math>P/Z</math> must be cyclic. Then, by fact (3), <math>P</math> would be abelian, but this would imply that <math>Z = P</math>, in which case the order of <math>Z</math> would have been <math>p^3</math>.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CD3 || The order of <math>Z</math> is either <math>p</math> or <math>p^3</math> || Fact (4) || <math>P</math> has order <math>p^3</math> || Steps (CD1), (CD2) || <toggledisplay>By fact (4), the order of <math>Z</math> must divide the order of <math>P</math>. The only possibilities are <math>1,p,p^2,p^3</math>. Step (CD1) eliminates the possibility of <math>1</math>, and step (CD2) eliminates the possibility of <math>p^2</math>. This leaves only <math>p</math> or <math>p^3</math>.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CD4 ||If <math>Z</math> has order <math>p</math>, then <math>Z</math> is cyclic of order <math>p</math> and the quotient <math>P/Z</math> is elementary abelian of order <math>p^2</math> || Facts (2), (3), (4), (5), (6) || <math>P</math> has order <math>p^3</math>. || || <toggledisplay>If <math>Z</math> has order <math>p</math>, then by fact (5), <math>Z</math> must be cyclic. <math>P/Z</math> exists by Fact (2) and its order is <math>|P|/|Z| = p^3/p = p^2</math> by Fact (4). By fact (3), <math>P/Z</math> cannot be cyclic, because if it were cyclic, then <math>P</math> would be abelian, which would mean that <math>Z = P</math> has order <math>p^3</math>. Thus, <math>P/Z</math> is a ''non-cyclic'' group of order <math>p^2</math>. By fact (6), the only non-cyclic group of order <math>p^2</math> is the elementary abelian group, so <math>P/Z</math> must be the elementary abelian group of order <math>p^2</math>.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CD5 || If <math>Z</math> has order <math>p^3</math>, <math>P</math> is abelian. || || <math>P</math> has order <math>p^3</math>. || || <toggledisplay>We get <math>P = Z</math>, so <math>P</math> is abelian.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CD6 || We get the desired result. || || || Steps (CD3), (CD4), (CD5) || Step-combination. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 79: | Line 126: | ||

! Step no. !! Assertion/construction !! Facts used !! Given data used !! Previous steps used !! Explanation | ! Step no. !! Assertion/construction !! Facts used !! Given data used !! Previous steps used !! Explanation | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CN1 || The derived subgroup (commutator subgroup) <math>P'</math> equals <math>Z</math>, so <math>P</math> has class two. || || <math>P</math> is non-abelian of order <math>p^3</math>. || <math>P/Z</math> is abelian, <math>Z</math> has order <math>p</math>. || <toggledisplay>Since <math>P/Z</math> is abelian, <math>P'</math> is contained in <math>Z</math>. Since <math>Z</math> has prime order, the only possible subgroups are the trivial subgroup and <math>Z</math> itself. The derived subgroup cannot be trivial since <math>P</math> is non-abelian, hence the derived subgroup must be <math>Z</math>. Note that this forces <math>P</math> to have class two.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CN2 || We can find elements <matH>a,b \in P</math> such that the images of <math>a,b</math> in <math>P/Z</math> are non-identity elements of <math>P/Z</math> that generate it. || || || <math>P/Z</math> is elementary abelian of order <math>p^2</math> || <toggledisplay><math>P/Z</math> is elementary abelian of order <math>p^2</math>, hence is generated by a set of size two comprising non-identity elements. Choose <math>a,b</math> to be arbitrary inverse images of these elements.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CN3 || <math>Z,a,b</math> together generate <math>P</math>. || || || Step (CN2) || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CN4 || <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> do not commute. || || || Steps (CN2), (CN3) || <toggledisplay>If <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> commute, then <math>C_P(a)</math> contains <math>Z,a,b</math>, hence equals all of <math>P</math>. Thus, <math>a \in Z</math>, so its image in <math>P/Z</matH> is the identity element, a contradiction to what we assumed.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CN5 || Let <math>z = [a,b]</math>. Then, <math>z</math> is a non-identity element of <math>Z</math> and <math>\langle z \rangle = Z</math>. || || || Steps (CN1), (CN4) || <toggledisplay>We must have <math>z \in P'</math>, which equals <math>Z</math> by Step (1). By Step (4), <math>[a,b]</math> is not the identity element. So <math>z</math> is a non-identity element of <math>Z</math>. Further, since <math>Z</math> has order <math>p</math>, it has no proper nontrivial subgroups, so <math>\langle z \rangle</math> must equal all of <math>Z</math>.</toggledisplay> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | CN6 || The elements <math>a,b</math> both have order either <math>p</math> or <math>p^2</math>. Also, the elements <math>a^p</math> and <math>b^p</math> are both in <math>Z</math>. || || || || <toggledisplay>The order of <math>a</math> must divide the order of the group, which is <math>p^3</math>. It cannot equal <math>p^3</math>, because that would make the group cyclic and hence abelian. It cannot equal <math>1</math>, because <math>a</math> is a non-identity element. The only possibilities are <math>p</math> and <math>p^2</math>. Also, the image of <math>a</math> in <math>P/Z</math> has order <math>p</math> because <math>P/Z</math> is elementary abelian, so <math>a^p \in Z</math>. The same goes for <math>b</math>.</toggledisplay> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 100: | Line 147: | ||

<math>\langle a,b,z \mid a^p = b^p = z^p = e, az = za, bz = zb, [a,b] = z \rangle</math> | <math>\langle a,b,z \mid a^p = b^p = z^p = e, az = za, bz = zb, [a,b] = z \rangle</math> | ||

These relations already restrict us to order at most <math>p^3</math>, because we can use the commutation relations to express every element in the form <math>a^\alpha b^\beta z^\gamma</math>, where <math>\alpha,\beta,\gamma</math> are integers mod <math>p</math>. To show that there is no further reduction, we note that there is a group of order <math>p^3</math> satisfying all these relations, namely [[ | These relations already restrict us to order at most <math>p^3</math>, because we can use the commutation relations to express every element in the form <math>a^\alpha b^\beta z^\gamma</math>, where <math>\alpha,\beta,\gamma</math> are integers mod <math>p</math>. To show that there is no further reduction, we note that there is a group of order <math>p^3</math> satisfying all these relations, namely [[unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p)]]. This is the multiplicative group of unipotent upper-triangular matrices with entries from the field of <math>p</math> elements. | ||

Thus, Case A gives a unique isomorphism class of groups. Note that the analysis so far works both for <math>p = 2</math> and for odd primes. The nature of the group obtained, though, is different for <math>p = 2</math>, where we get [[dihedral group:D8]] which has exponent <math>p^2</math>. For odd primes, we get a [[group of prime exponent]]. | Thus, Case A gives a unique isomorphism class of groups. Note that the analysis so far works both for <math>p = 2</math> and for odd primes. The nature of the group obtained, though, is different for <math>p = 2</math>, where we get [[dihedral group:D8]] which has exponent <math>p^2</math>. For odd primes, we get a [[group of prime exponent]]. | ||

| Line 106: | Line 153: | ||

'''Case B''': <math>a</math> has order <math>p^2</math>, <math>b</math> has order <math>p</math> | '''Case B''': <math>a</math> has order <math>p^2</math>, <math>b</math> has order <math>p</math> | ||

In this case, we first note that <math>a^p \in Z = \langle z \rangle</math>. Since <math>a^p</math is a non-identity element, there exists nonzero <math>r</math> (taken mod <math>p</math>) such that <math>a^p = z^r</math>. Consider the element <math>c = b^r</math> Then, by Fact (8), and the observation that <math>P</math> has class two (Step (1) in the above table), we obtain: | In this case, we first note that <math>a^p \in Z = \langle z \rangle</math>. Since <math>a^p</math> is a non-identity element, there exists nonzero <math>r</math> (taken mod <math>p</math>) such that <math>a^p = z^r</math>. Consider the element <math>c = b^r</math> Then, by Fact (8), and the observation that <math>P</math> has class two (Step (1) in the above table), we obtain: | ||

<math>\! [a,c] = [a,b^r] = [a,b]^r = z^r = a^p</math> | <math>\! [a,c] = [a,b^r] = [a,b]^r = z^r = a^p</math> | ||

| Line 133: | Line 180: | ||

! Case letter !! What it means !! Isomorphism class of group for <math>p = 2</math> !! Isomorphism class of group for odd prime | ! Case letter !! What it means !! Isomorphism class of group for <math>p = 2</math> !! Isomorphism class of group for odd prime | ||

|- | |- | ||

| A || Both <math>a,b</math> have order <math>p</math> || [[dihedral group:D8]] || [[ | | A || Both <math>a,b</math> have order <math>p</math> || [[dihedral group:D8]] || [[unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p)]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| B, B2 || One of the elements has order <math>p^2</math>, the other has order <math>p</math> || [[dihedral group:D8]] || [[semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order]] | | B, B2 || One of the elements has order <math>p^2</math>, the other has order <math>p</math> || [[dihedral group:D8]] || [[semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order]] | ||

| Line 143: | Line 190: | ||

* [[Dihedral group:D8]] and [[quaternion group]] are non-isomorphic: The latter has no non-central element of order two, for instance. | * [[Dihedral group:D8]] and [[quaternion group]] are non-isomorphic: The latter has no non-central element of order two, for instance. | ||

* [[ | * [[Unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p)]] and [[semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order]] are non-isomorphic: The former has exponent <math>p</math>, the latter has exponent <math>p^2</math>. | ||

Latest revision as of 04:25, 24 February 2016

Statement

Let be a prime number. Then there are, up to isomorphism, five groups of order . These include three abelian groups and two non-abelian groups. The nature of the two non-abelian groups is somewhat different for the case .

For more information on side-by-side comparison of the groups for odd primes, see groups of prime-cube order. For information for the prime 2, see groups of order 8

The three abelian groups

The three abelian groups correspond to the three partitions of 3:

| Partition of 3 | Corresponding abelian group | GAP ID among groups of order |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | cyclic group of prime-cube order, denoted or , or | 1 |

| 2 + 1 | direct product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order, denoted or | 2 |

| 1 + 1 + 1 | elementary abelian group of prime-cube order, denoted , or , or | 5 |

The two non-abelian groups

For the case , these are dihedral group:D8 (GAP ID: (8,3)) and quaternion group (GAP ID: (8,4)).

For the case of odd , these are unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p) (GAP ID: (,3)) and semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order (GAP ID: (,4)).

Related facts

- Classification of nilpotent Lie rings of prime-cube order

- Classification of groups of prime-square order

- Classification of Lie rings of prime-square order

Facts used

The table below lists key facts used directly and explicitly in the proof. Fact numbers as used in the table may be referenced in the proof. This table need not list facts used indirectly, i.e., facts that are used to prove these facts, and it need not list facts used implicitly through assumptions embedded in the choice of terminology and language.

| Fact no. | Statement | Steps in the proof where it is used | Qualitative description of how it is used | What does it rely on? | Difficulty level | Other applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prime power order implies not centerless | Step (CD1) | Eliminates the case of trivial center | class equation of a group | click here | |

| 2 | Center is normal | Steps (CD2), (CD4) | Used to note that the quotient by the center exists as a group | click here | ||

| 3 | Cyclic over central implies abelian | Steps (CD2) (CD4) | Rules out the possibility of center of order , helps determine nature of quotient group if center has order | click here | ||

| 4 | Lagrange's theorem | Step (CD2) | Narrows down possibilities for order of center, and allows for computation of order of quotient group | 2 | click here | |

| 5 | Equivalence of definitions of group of prime order: This basically states that any group of prime order must be cyclic. | Steps (CD2), (CD4) | Helps rule out center of order , helps determine isomorphism class of center of order | click here | ||

| 6 | Classification of groups of prime-square order | Step (CD4) | Narrows down possibilities for quotient by the center once we have determined that the center has order | click here | ||

| 7 | Structure theorem for finitely generated abelian groups | Classification of abelian groups case | click here | |||

| 8 | Class two implies commutator map is endomorphism | Case B analysis | Helps reduce general case to a specific presentation by a change of variable | click here | ||

| 9 | Formula for powers of product in group of class two | Case C analysis | Helps reduce Case C to Case B by a change of variable | click here |

Cohomology tree

This can be formulated as an alternative proof if we prove assertions for each of the cohomology groups.

For odd primes

The cohomology groups governing the branchings are as follows:

- Second cohomology group for trivial group action of group of prime order on group of prime order controls the initial branching from the root.

- Second cohomology group for trivial group action of elementary abelian group of prime-square order on group of prime order controls the upper second level branching.

- Second cohomology group for trivial group action of cyclic group of prime-square order on group of prime order controls the lower second level branching.

For the prime 2

This is for groups of order 8:

The cohomology groups governing the branchings are as follows:

- Second cohomology group for trivial group action of Z2 on Z2 controls the initial branching from the root.

- Second cohomology group for trivial group action of V4 on Z2 controls the upper second level branching.

- Second cohomology group for trivial group action of Z4 on Z2 controls the lower second level branching.

Proof

This proof uses a tabular format for presentation. Provide feedback on tabular proof formats in a survey (opens in new window/tab) | Learn more about tabular proof formats|View all pages on facts with proofs in tabular format

First part of proof: crude descriptions of center and quotient by center

Given: A prime number , a group of order .

To prove: Either is abelian, or we have: is a cyclic group of order and is an elementary abelian group of order

Proof: Let be the center of .

| Step no. | Assertion/construction | Facts used | Given data used | Previous steps used | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD1 | is nontrivial | Fact (1) | has order , specifically, a power of a prime | Fact+Given direct | |

| CD2 | The order of cannot be | Facts (2), (3), (4), (5) | has order | [SHOW MORE] | |

| CD3 | The order of is either or | Fact (4) | has order | Steps (CD1), (CD2) | [SHOW MORE] |

| CD4 | If has order , then is cyclic of order and the quotient is elementary abelian of order | Facts (2), (3), (4), (5), (6) | has order . | [SHOW MORE] | |

| CD5 | If has order , is abelian. | has order . | [SHOW MORE] | ||

| CD6 | We get the desired result. | Steps (CD3), (CD4), (CD5) | Step-combination. |

Second part of proof: classifying the abelian groups

This classification follows from fact (7): the abelian groups of order correspond to partitions of 3, as indicated in the original statement of the classification.

Third part of proof: classifying the non-abelian groups

Given: A non-abelian group of order . Let be the center of .

Previous steps: is cyclic of order , and is elementary abelian of order .

We first make some additional observations.

| Step no. | Assertion/construction | Facts used | Given data used | Previous steps used | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN1 | The derived subgroup (commutator subgroup) equals , so has class two. | is non-abelian of order . | is abelian, has order . | [SHOW MORE] | |

| CN2 | We can find elements such that the images of in are non-identity elements of that generate it. | is elementary abelian of order | [SHOW MORE] | ||

| CN3 | together generate . | Step (CN2) | |||

| CN4 | and do not commute. | Steps (CN2), (CN3) | [SHOW MORE] | ||

| CN5 | Let . Then, is a non-identity element of and . | Steps (CN1), (CN4) | [SHOW MORE] | ||

| CN6 | The elements both have order either or . Also, the elements and are both in . | [SHOW MORE] |

We now make cases based on the orders of and . Note that these cases may turn out to yield isomorphic groups, because the cases are made based on and , and there is some freedom in selecting these.

Case A: and both have order .

In this case, the relations so far give the presentation:

These relations already restrict us to order at most , because we can use the commutation relations to express every element in the form , where are integers mod . To show that there is no further reduction, we note that there is a group of order satisfying all these relations, namely unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p). This is the multiplicative group of unipotent upper-triangular matrices with entries from the field of elements.

Thus, Case A gives a unique isomorphism class of groups. Note that the analysis so far works both for and for odd primes. The nature of the group obtained, though, is different for , where we get dihedral group:D8 which has exponent . For odd primes, we get a group of prime exponent.

Case B: has order , has order

In this case, we first note that . Since is a non-identity element, there exists nonzero (taken mod ) such that . Consider the element Then, by Fact (8), and the observation that has class two (Step (1) in the above table), we obtain:

Consider the presentation:

We see that all these relations are forced by the above, and further, that this presentation defines a group of order , namely semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order.

Thus, there is a unique isomorphism class in Case B. Note that the analysis so far works both for and for odd primes. The nature of the group, though, is different for , we get dihedral group:D8, which is the same isomorphism class as Case A.

Case B2: has order , has order .

Interchange the roles of and replace by and we are back in Case B.

Case C: and both have order .

By Fact (9), we can show that for odd prime, it is possible to make a substitution and get into Case B. PLACEHOLDER FOR INFORMATION TO BE FILLED IN: [SHOW MORE]

For , working out the presentation yields quaternion group.

Here is a summary of the cases:

| Case letter | What it means | Isomorphism class of group for | Isomorphism class of group for odd prime |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Both have order | dihedral group:D8 | unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p) |

| B, B2 | One of the elements has order , the other has order | dihedral group:D8 | semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order |

| C | Both elements have order | quaternion group | semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order |

Finally, we note that:

- Dihedral group:D8 and quaternion group are non-isomorphic: The latter has no non-central element of order two, for instance.

- Unitriangular matrix group:UT(3,p) and semidirect product of cyclic group of prime-square order and cyclic group of prime order are non-isomorphic: The former has exponent , the latter has exponent .

![{\displaystyle z=[a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5566995bf8afcb63d83e13ab13e7d753d0db0be9)

![{\displaystyle [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

![{\displaystyle \langle a,b,z\mid a^{p}=b^{p}=z^{p}=e,az=za,bz=zb,[a,b]=z\rangle }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2ac6dd00965102f89a1ca60f482f8b617be79529)

![{\displaystyle \![a,c]=[a,b^{r}]=[a,b]^{r}=z^{r}=a^{p}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0de9937cf2215e28f2f9a39da68aaf076a500617)

![{\displaystyle \langle a,c\mid a^{p^{2}}=c^{p}=e,[a,c]=a^{p}\rangle }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a2f34dbaac9833749b98047cf8e6a85f5605971a)