What on earth is a group?

This is an entertainment resource, and is intended as a supplementary, or add-on, feature to the main wiki

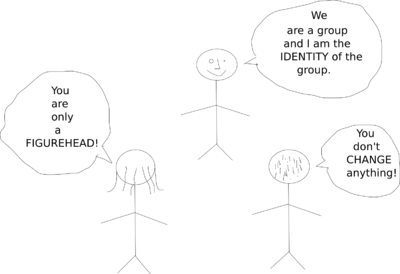

This is a (comical, and hypothetical) conversation between a mathematician (M) and an ordinary person (P), as the mathematician tries to explain the notion of group to the ordinary person.

Part 1: Basic definitions and setup

This corresponds to material covered in the first part of the Groupprops guided tour for beginners.

Episode one (Name-throwing)

P: So what kind of math do you work on?

M: As of now, I'm interested in group theory. That's basically the study of a mathematical notion called group.

P: Oh... so what are groups? I daresay it is just a name coincidence, but do groups have anything to do with groups of people?

M: No, hardly. The word "group" doesn't have any specific rationale. A group is just a collection of elements, with some operations and additional structure.

P: Okay, so it's the group, as opposed to the individual?

M: Not quite. You can have a group with just one element.

P: Strange! Can you have a group with no elements?

M: No, that isn't allowed.

P: So your groups have these elements, as you call them, and then these elements play around with each other. So are all the elements of your group equal, or are there some that are better than others?

M: Yes and no, I guess. In some sense, all elements of the group are equal, but in others, they aren't.

P: I'm confused.

M: If you were dealing with a group of people, would you say they're all equal, or that they're different?

P: Depends on what parameter you're looking at. People are different, but in some ways, we're all the same.

M: Exactly.

P: Okay, so does every group have a leader?

M: Yes, that's called the identity element. The leader doesn't depend on the group, but the group depends on the leader. In fact, the leader can stay all alone without the rest of the group, though that would make it trivial.

P: Okay, so there's this dependence on the leader? And what mechanisms does the leader use to exert authority?

M: Interestingly, the leader exerts authority through humility. Basically, the leader always multiplies any other element of the group to itself, so the leader just reflects back to every other element what it already is.

P: Interesting. So can you partition your group into subgroups?

M: No, far from it! There is a notion of subgroup, but every subgroup must contain the identity element. So we can't divide the group into subgroups.

P: So to what extent does the leader determine the way the group behaves?

M: Not at all! The leader is crucial to the existence of the group, but in no way affects the structure of the group. The leader's more like a figurehead, if you like.

P: That's interesting. And you say these kind of things are useful in mathematics?

M: Yeah.

Episode two (defining the operations)

P: So tell me more about the way these things called groups work out.

M: Do you really want to know?

P: Yes, at the philosophical level, I guess.

M: Last time, I'd talked about a group, which was like a collection of elements with some operations. There's one distinguished figurehead called the identity element. Any subgroup has to contain the identity element, so basically everything depends on the identity element. But the identity element doesn't actually influence anything else. It's just a statutory requirement.

P: So what are the operations happening?

M: There's an operation called multiplication, where basically two elements go in and a third one comes out. And if one of the two elements going in is the figurehead, you just get the other one.

P: By a third one, you mean another element of the same group?

M: Yes, exactly. And moreover, every element has an inverse. An inverse of an element is something else so that, if they get together, they output the figurehead.

P: This seems to make little sense ... do I get it as saying that for every person, there's a different person such that together, they're as powerful as the figurehead.

M: No, not really. You shouldn't think of groups as power plays. Everything's equal. In fact, you can go from any element to any other element, by multiplying by some third element. And that third element is unique.

P: So to every pair of people, there's a third person?

M: Not really, it also depends on how the pair is ordered. Some groups are Abelian, all the elements commute, so the above is correct. In others, things depend on the order in which you pair things.

P: So it's like one in the pair is more important than the other?

M: No! The order matters but there's no one that's intrinsically more important than the other. It's just a matter of convention. Like left versus right.

P: Okay, I'm getting tired of this.

Episode three (the conditions that the operations must satisfy)

P: Your groups have been giving me nightmares. It seems a weird society.

M: Actually, it's pretty straightforward.

P: Okay, I'll try one last time to understand.

M: A group's basically just a set of things, with some operations defined on it.

P: What kind of things?

M: You shouldn't worry about that. The kind of things don't matter. They're just elements of the group, it doesn't matter if they're humans or rabbits or stones.

P: But then anything is a group, right?

M: Right. The structure of a group doesn't stem so much from what its elements look like, as it does from the way the operations are defined.

P: You keep throwing around the word operations. What does it really mean?

M: It's something that takes things from the group as input and throws things in the group as output.

P: So it's a kind of change? Like a group evolving through constant operation?

M: No, I think you're thinking too much in terms of time and evolution. Groups don't change with time. They're a set of elements (static little things, which we don't really care about). And there are some operations. The operations are rules that say: if you put in so-and-so elements, you get out so-and-so elements. Like the operation of addition has a rule: if you put in 3 and 4, you get 7.

P: And the operations aren't actually happening?

M: Nothing's happening. It's just a set with some operations.

P: Any kind of operations?

M: No. Remember, last time, I talked about the "product" of two things? That takes in two things in a specific order and gives out a third thing. It's like multiplying numbers, except that the things you're multiplying need not be numbers.

P: So a group is a set with product operations?

M: A group is a set with one product operation. And that operation has to behave well with the identity element of the group. The identity element multipled with any other element, must give that second element. And finally you've got to have inverses. For every element, there's going to be another element that, together with it, gives the identity.

P: A product, with identity element and inverses. Is that a group?

M: There's a rule called associativity of composition. Which is that if you multiply and , and then multiply by , it's the same as multiplying with the product of and .

P: Isn't that obvious? I seem to remember doing that in middle school.

M: It's true for numbers. But since we're taking a set with any kind of objects, we need to state it explicitly.

P: Okay, I'll believe that. Could you go over it again?

M: A group is a set with a multiplication that is associative, with an identity element that doesn't change anything when multiplied, and where every element has an inverse.

P: Phew! Let me try that. A group is a set with a multiplication that is associative, with an identity element that doesn't change anything when multiplied, and where every element has an inverse.

M: Right.

P: I'm not exactly sure I understand that. But at least it seems to make some sense.

Episode four (consolidation of group)

M: So do you remember what a group is?

P: Sort of. It's like this set of things, you don't really care what they are, and you have this multiplication that takes in two things and gives something out, and you have this identity that does nothing, and you have these things called inverses.

M: Yes, that's good.

P: I'm not sure I really understand inverses though.

M: It's the thing you do to cancel the element. Like the inverse of 5 under multiplication is 1/5.

P: Okay, so when you feed in something and its inverse, you get the identity. Makes a bit of sense.

M: But you should be careful about the order in which you multiply things. Multiplying with doesn't give the same result as multiplying with .

P: Which one's better?

M: Neither. They're both different. That's all. In technical jargon we say that and commute if the product both ways is the same.

P: Commute?

M: Like, we can move the and across each other.

P: Across each other?

M: So the typical way of writing the product of and is like . So what commutativity says is that .

P: And does commutativity happen in groups?

M: Sometimes. But there's no guarantee that it'll happen.

P: You mean, if it happens, it happens by sheer chance.

M: Not sheer chance, but yes, it isn't guaranteed. A group where any two elements commute is called an Abelian group. Most of the groups you've seen, like integers under addition, are Abelian groups.

P: Addition? I thought the group operation was multiplication.

M: The group operation's just a binary operation. We don't really care whether it is addition or multiplication, as long as it satisfies the laws.

P: What laws?

M: Associativity, the existence of an identity element, and the existence of inverses.

Episode five (subgroup and trivial group)

P: You know, I'm beginning to think I understand groups.

M: That's nice.

P: Let me see. A group with a set with an associative multiplication, where there's an identity element that doesn't change the thing it multiplies with, and where everything has an inverse.

M: Spot on.

P: Phew. That seems a fair bit of stuff.

M: Do you remember what the trivial group is?

P: The empty group?

M: A group can't be empty.

P: Why not?

M: It's got to have an identity element.

P: Oh right. So the trivial group is the group with nothing but the identity?

M: Yeah, it's got nothing but its own ego.

P: Interesting. And I also vaguely remember you mentioning subgroups.

M: They're subsets that are closed under the group operations.

P: Closed under?

M: I mean, it's a subset of the group such that if you feed in two things from the subset, you get back something in the subset. And it should have the identity element and the inverse of anything in the subset is in the subset.

P: So it's self-sufficient? Doesn't need anything from outside?

M: Yes, exactly.

P: But to be self-sufficient, it's got to contain the identity element, the "ego" of the group?

M: Yes, I think you're getting a feel for groups.

P: Hope so. It's kind of hard to imagine these static things with arbitrary operations that have to satisfy some arbitrary rules.

M: There's actually good reason for those rules.

P: I'll believe you.

Mathematical upshot:

- A group is a set with some additional structure.

- The additional structure is a binary operation (called multiplication). The binary operation is associative, has an identity element, and every element of the group has inverses.

- That's all a group is. There's no special sanctity to the elements of the group. What really matters for group structure is the way the binary operations are defined.

- The group multiplication need not be commutative. If it is, we say that the group is an Abelian group.

- A group cannot be empty. It always contains the identity element. The smallest possible group is the trivial group -- the group with only one element, which is the identity element.

- A subgroup of a group is a subset that is closed under the group multiplication, has the identity element, and is closed under taking inverses.