Understanding the cycle decomposition: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

* The function <math>x \mapsto 2x</math> on the set of integers. This is injective, but ''not'' surjective: its image is the set of even integers. The picture makes this clear. | * The function <math>x \mapsto 2x</math> on the set of integers. This is injective, but ''not'' surjective: its image is the set of even integers. The picture makes this clear. | ||

* The function that sends <math>x</math> to <math>x/2</math> if <math>x</math> is even and to <math>x</math> if <math>x</math> is odd. This is ''surjective'' (every element is the image of its double) but is ''not'' injective (the odd numbers have two incoming edges). | * The function that sends <math>x</math> to <math>x/2</math> if <math>x</math> is even and to <math>x</math> if <math>x</math> is odd. This is ''surjective'' (every element is the image of its double) but is ''not'' injective (the odd numbers have two incoming edges). | ||

| Line 79: | Line 78: | ||

When <math>S</math> is infinite, cycles are not the only possibility. It is also possible that applying <math>f</math> repeatedly ''never'' returns to the original point. An example is the translation map on the group of integers: the map <math>x \mapsto x + 1</math>. Here, iterating the permutation keeps the point moving to the right, and there is no looping back. | When <math>S</math> is infinite, cycles are not the only possibility. It is also possible that applying <math>f</math> repeatedly ''never'' returns to the original point. An example is the translation map on the group of integers: the map <math>x \mapsto x + 1</math>. Here, iterating the permutation keeps the point moving to the right, and there is no looping back. | ||

[[Image:Cycledecomposition3.png]] | |||

If there is no looping back, we can also go ''backward'' for an infinite duration without looping back. For instance, for the map <math>x \mapsto x + 1</math>, for which there is no looping back, the inverse map <math>x \mapsto x - 1</math> ''also'' has no looping back. Thus, instead of a cycle, we obtain a straight chain extending indefinitely in both directions. | If there is no looping back, we can also go ''backward'' for an infinite duration without looping back. For instance, for the map <math>x \mapsto x + 1</math>, for which there is no looping back, the inverse map <math>x \mapsto x - 1</math> ''also'' has no looping back. Thus, instead of a cycle, we obtain a straight chain extending indefinitely in both directions. | ||

Revision as of 20:41, 1 December 2008

This is a survey article related to:cycle decomposition for permutations

View other survey articles about cycle decomposition for permutations

A permutation on a set is a bijective map from to itself. There are many ways of describing permutations: one way is to give a formula for the function; another is to write the permutation down using the one-line or two-line notation. However, these ways of writing permutations down often fail to provide a feel for the dynamics of a permutation, and its group-theoretic nature.

The cycle decomposition of a permutation is a form of expressing the permutation that captures its dynamics as well as its group-theoretic behavior. This survey article builds the idea of cycle decompositions in a number of ways, and provides some useful examples.

The directed graph associated with a function

Description of the directed graph

Suppose is a set and is a function. We define the directed graph associated with as follows.

- The vertices, or points, or nodes, of the graph are the elements of . In other words, we begin by drawing all the elements of as separate points.

- There is a directed edge from a vertex to a vertex if and only if . Note that if , we get a directed edge from to itself -- this is called a loop.

Notice the following:

- Since is a function, there is a unique value of for every . Thus, there is a unique directed edge coming out from , and this edge is headed towards .

- The edges coming to represent all the points such that .

- is injective if and only if, for every , there is at most one edge entering .

- is surjective if and only if, for every , there is at least one edge entering .

- is bijective if and only if, for every , there is exactly one edge entering .

Finite examples

Suppose is the set and the function is defined by:

.

The directed graph associated with looks like this:

Notice that is neither injective nor surjective. Both and map to , leading to the vertex having an indegree of two -- two incoming edges. On the other hand, the vertices and have indegrees of zero -- there are no incoming edges to these vertices.

In contrast, consider the function:

.

This function is bijective, and the graph clearly shows this:

Infinite examples

In the infinite case, there are examples of functions that are injective and not surjective, and there are also examples of functions that are surjective but not injective. Here are some, along with finite fragments of their graphs:

- The function on the set of integers. This is injective, but not surjective: its image is the set of even integers. The picture makes this clear.

- The function that sends to if is even and to if is odd. This is surjective (every element is the image of its double) but is not injective (the odd numbers have two incoming edges).

The inverse of a bijective function

If is bijective, i.e., is a permutation, the directed graph associated with has the property that every vertex has indegree one and every vertex has outdegree one. Further, there is a simple relation between the graph of and the graph of .

For any , is the unique satisfying . In other words, it is the starting point of the directed edge that ends at . This suggests that if we reverse the direction of the edge, we get an edge sending to .

The upshot: given a bijective function, the directed graph of the inverse function is obtained by simply reversing the direction on all edges in its directed graph.

Iteration and dynamics

Another advantage of the directed graph is that it helps see what happens on iterating the function. To understand this, recall that to know , we need to start at and flow along the unique edge emanating from . Thus, to find , we need to first reach , and then flow along the unique edge emanating from that point. More generally, to find , we need to start at and move forward steps along the edges of the graph.

The cycle decomposition: how it can loop back

We already understand the local picture for the directed graph associated with a permutation. Let's try to understand the implications of this picture more closely.

Suppose is a permutation (i.e., a bijective function). Suppose I start at a point and consider the sequence of points . Essentially, I start at the point and move forward along the edges of the graph.

Notice the following: if I ever repeat a point, the first point I repeat must be . To see this, observe that if , and , then , and the injectivity of yields that . A downward induction thus shows that .

This can also be seen pictorially: the graph cannot loop back to a point other than , because this point already has an incoming edge. Thus, the graph must loop back to itself, or not loop back at all.

Note that when is not injective, the graph can cycle back to a point other than , giving a classic shape.

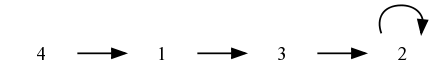

The cycle decomposition: cycles or chains

When is a finite set and is a permutation of , we know that if we start moving along from any vertex along the graph, we'll eventually repeat a vertex. The remarks made above thus show that we get a cycle at .

When is infinite, cycles are not the only possibility. It is also possible that applying repeatedly never returns to the original point. An example is the translation map on the group of integers: the map . Here, iterating the permutation keeps the point moving to the right, and there is no looping back.

If there is no looping back, we can also go backward for an infinite duration without looping back. For instance, for the map , for which there is no looping back, the inverse map also has no looping back. Thus, instead of a cycle, we obtain a straight chain extending indefinitely in both directions.

Note that for an injective map (as opposed to a bijective map) there may exist chains that extend indefinitely in the forward direction, but can be extended only to a finite extent in the backward direction. An example is the map on the set of positive integers.

The cycle decomposition: obtaining the decomposition

We've seen that starting from any element , we can trace either a cycle or a chain containing , obtained by following the flow of the edges. Explicitly, the cycle of gives, in (cyclic) sequence the points .

Since every element has its own unique cycle or chain, the cycles and chains form a partition of the whole set . In the finite case, there are no chains, so the set is partitioned as a union of disjoint cycles.

Here is another way of thinking about the cycle decomposition. We start with a point and trace the cycle of . Note that for any point in the cycle of , the cycle of that point is the same as the cycle of . Now, if the cycle contains all points of , we are done. Otherwise, pick a point not in the cycle, and trace its cycle. This cycle cannot intersect the previous cycle, since that would contradict the fact that there is a unique edge coming into every vertex. Thus, we get a new cycle, that covers some new elements. We repeat this process until the whole finite set is covered.

In infinite sets, this repeat until idea cannot be used in a naive sense, but the more sophisticated idea of being in the same cycle as an equivalence relation works.